The rise of OpenStreetMap: A quest to conquer Google’s mapping empire

Making a good map

Google Maps is the big dog with billions of dollars at its disposal and plenty of incentive to ensure Google Maps is in tip-top shape. And OSM is the people-powered underdog, powered by unpaid volunteers. There must surely be large swathes of land not covered by OpenStreetMap?

“Actually no, not that a consumer would notice,” says Coast. “As a display map that you would just look at, OpenStreetMap is pretty complete.

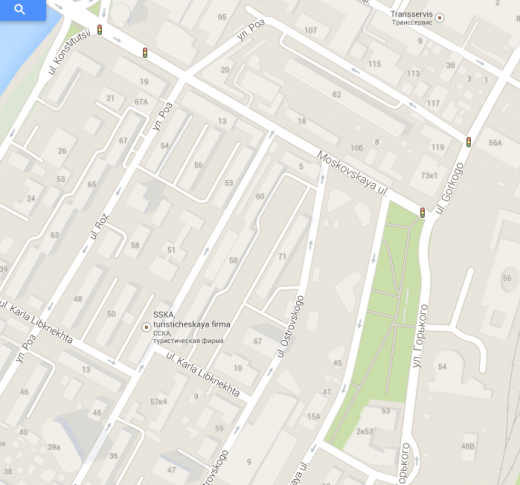

A quick search on the OpenStreetMap Web portal for ‘Sochi’, the location of the 2014 Winter Olympics, reveals that it is pretty complete. And compared with Google Maps, it could be argued it’s actually more extensive.

But what about the darkest corners of Siberia and other such remote locations? “You’d be amazed – places are mapped approximately to the limit, and it would be hard to find anywhere that OSM lacks decent data,” says Coast. “Most of the time it will have either the best, or a very close second for most of the world.”

So if OSM is actually more extensive than Google Maps some of the time, why would any company or consumer use Google Maps over an OpenStreetMap-powered competitor? Well, it seems that it’s not all about the maps and the coverage. The data attached to the maps is every bit as important.

There are basically three core things that go into any good map – there’s the display element (the map itself), and the navigability information within the map (speed-limits, one-way etc) that help you build software for turn-by-turn navigation. And the third piece of the jigsaw is addresses – where are all the houses, and what are the numbers on each house?

“OpenStreetMap is very good at the display part, and it has pretty good navigability information, though it’s not perfect,” says Coast. “But then there’s the address data – this is missing from many parts of OpenStreetMap. You need all three pieces to offer consumer turn-by-turn navigation, and that’s what we’ve been working on at Telenav – filling in those two pieces.”

Like a good wine, online maps improve with age. One of the things that Skobbler, Telenav and others do is gather lots of GPS traces and process it to figure out things for themselves, and this doesn’t require direct user input.

For example, when drivers use these apps while driving along London’s South Circular, GPS data may reveal that most people drive at 60mph along a certain stretch, which means the speed-limit is probably 60mph. Similarly, it can detect if all cars are traversing the same route in the same direction, therefore it’s almost certainly a one-way road.

“Without having to send people out or get volunteers, we can process lots of data to figure things out,” says Coast. “And that’s what we do to make OpenStreetMap better for turn-by-turn navigation.”

Postal codes, on the other hand, are a different kettle of fish. Typically constituting a series of letters and/or numbers, these codes ultimately help letters arrive at the right house in the right town. The actual setup, however, varies from country-to-country. In the UK, a full alpha-numeric post code, or ‘postcode unit’, usually matches a handful of addresses (e.g. four houses), or a single, larger end-point such as a warehouse. But matching such data up within OpenStreetMap can be problematic.

The problem lies in not being able to convert a postcode to a latitude/longitude figure, and then back again. The data to easily enable this isn’t freely available in many countries.

“It’s very hard to reverse engineer them, because you can figure out streets just by walking around, you can see names on signs,” says Coast. “But if you’re just walking around trying to figure out what post code it is, that’s more difficult.”

Indeed, another side-project Coast started some years back was called Free The Postcode, the idea being that if you’re sitting in a pub you just ask the guy behind the bar what the postcode at the pub. And there’s no shortage of pubs, so eventually you can start to complete where all the postcodes are. “You’re never going to get 100% accuracy doing it in such a way,” says Coast. “But you’ll get pretty close.”

In terms of other countries, well, it’s much the same. Each has their own nuances in terms of how much postal code data is available. And this is one of the major stumbling blocks for OSM.

But address data isn’t the only stumbling block.

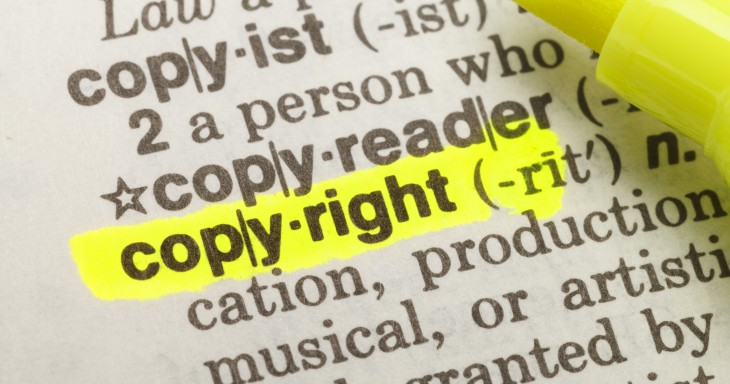

Attribution: Credit where credit’s due

“We’ve put a lot of time, effort and energy into making this project succeed, and we only ask two things in return,” says Coast. “One of them is if you change the data, please give us the changes back so we can improve the map.”

In other words, if a company taps OSM for its own services and edits the content to make it more accurate, the fundamental premise here is that they should make it available for everyone to benefit from. And what’s the second thing OSM want in return?

“If you use our data, can you please explicitly say, ‘hey, this is Open Street Map’,” continues Coast. “Because that means we’ll get more people using it, more people adding data, and this makes the maps better for everyone.”

However, it seems that people interpret that second clause rather narrowly. “What you see on most (non-OSM) maps is a little copyright of whoever built the map,” adds Coast. “For design reasons, (with OSM) some people want to do away with that line of text on the map – or just make it a tiny little link which then goes to a much broader set of attributions. Our interpretation is you should put ‘Copyright Open Street Map Contributors’ at the bottom right. I don’t think it’s a lot to ask.”

Indeed, in a forum post by OpenStreetMap Foundation Chairman Simon Poole, he cites lack of attribution as a major issue.

“Why is it that getting users of our data to attribute OpenStreetMap correctly seems to be such an uphill battle?,” he says. “This is not something new, browsing the wiki, mailing lists and forums show that this has been an issue from day one. Why is it so difficult for us to get the only compensation we ask for, when at the same time nobody has issues attributing Google?”

To rub salt into the wounds, Poole also says that it’s “not rare” to see a Google attribution on OpenStreetMap derived content. Ouch. But a quick peek at the OSM Foundation’s licensing terms reveal that they are pretty clear:

“We require that you use the credit “© OpenStreetMap contributors”.

You must also make it clear that the data is available under the Open Database License, and if using our map tiles, that the cartography is licensed as CC BY-SA. You may do this by linking to this copyright page. Alternatively, and as a requirement if you are distributing OSM in a data form, you can name and link directly to the license(s). In media where links are not possible (e.g. printed works), we suggest you direct your readers to openstreetmap.org (perhaps by expanding ‘OpenStreetMap’ to this full address), to opendatacommons.org, and if relevant, to creativecommons.org.”

What that actually translates to in real terms, it seems, is evidently open to interpretation – in terms of where the attribution actually appears. But it’s supposed to look a little something like this.

What that actually translates to in real terms, it seems, is evidently open to interpretation – in terms of where the attribution actually appears. But it’s supposed to look a little something like this.

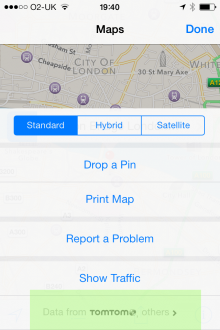

How this attribution ends up looking – if there is one at all – will vary from service to service. For example, with Apple – though it doesn’t exclusively use OSM data – you have to dig down quite deep into the acknowledgements to realize that OpenStreetMap data has been used.

You certainly wouldn’t know that it does just from looking at the maps, but then I guess things would start to look pretty ugly if Apple credited every source on the map itself.

For OpenStreetMap to gain more mindshare among the masses, it maybe does have to begin enforcing the attribution aspect a little more aggressively, or perhaps reword the licensing terms to make them less open to interpretation.

However, there is one other potential avenue open to OpenStreetMap, and that’s to launch its own branded, standalone service.