The rise of OpenStreetMap: A quest to conquer Google’s mapping empire

The rise of OpenStreetMap

The first building blocks of OpenStreetMap were cemented while Coast was at university in London back in 2004.

He dropped out of Computer Science and Physics degrees, and also worked in research departments of universities along the way, not to mention stints at software companies. Throw into the mix his own companies and a spell at Microsoft before joining Telenav last year and, well, it’s clear to see that Coast has had his fingers in many pies over the years.

But it’s OpenStreetMap we’re focusing on specifically here.

“The core way that the project works in terms of the infrastructure of the software was all stuff that I designed quite a long time ago now,” says Coast. “But it went through several iterations. The first two versions of the project were essentially thrown away and rewritten from scratch. But the third version is what lasted. We’re actually several versions on from that now, but the architecture and infrastructure as designed by me back then, is pretty much what you see today. It’s definitely faster and more scalable, but it’s the same stuff.”

The body that ‘calls the shots’, for want of a better phrase, with OpenStreetMap is the UK-registered OpenStreetMap Foundation. Now, the Foundation doesn’t actually have any paid employees as such, though there is around five hundred people who pay a nominal annual fee (£15/$25) to vote on things like who sits on the board.

The board currently consists of seven people, not including Coast himself who now has more of an advisory role. So how much work has gone into making OSM what it is today – and was this ever actually a full-time gig for Coast?

“It’s certainly been a full-time job, but just in different senses,” he says. “When I was a student, running OpenStreetMap consumed a large chunk of time building the thing initially. And then I was involved with a startup years ago, where effectively we were just working on OpenStreetMap all the time. And now I’m at Telenav, but really what we’re doing is OpenStreetMap work, and ensuring the data is up to scratch for use in consumer navigation.”

So while you probably couldn’t call OpenStreetMap a ‘job’ in itself for Coast, it’s certainly consumed many man hours and served to support other roles – including his current position at Telenav, which as we noted earlier is now the proud owner of Skobbler.

Founded in the US in 1999, Telenav offers a range of location-based services covering GPS navigation, localized search, and related services. But Telenav doesn’t commit itself to one map provider. “We’re kind of map agnostic,” says Coast. “We have relationships with Tom Tom, HERE, and OpenStreetMap.”

While Skobbler was working to improve OpenStreetMap data from its base in Europe, Telenav has been doing the same from its HQ in the States, which makes this acquisition begin to make a lot of sense. “There’s a good match there,” adds Coast. “But it also helps the company (Telenav) in a couple of ways – it helps us expand our office from being ‘US and China’, to having a solid base in Europe.”

So hand-in-hand, Telenav and Skobbler have been, and will continue to, improve OpenStreetMap data – primarily for its own products, of course, but the knock-on effect of this benefits anyone using the crowdsourced mapping platform.

Longer term, the Skobbler name will be gobbled up into the Telenav brand, while Skobbler’s existing apps such as GPS Navigation and Forever Map will remain the same for the time being, though these will likely be integrated into Telenav’s Scout-branded apps in the future.

It’s easy to call OpenStreetMap the ‘Wikipedia of maps’, and then be on your way. It’s to-the-point, simple to digest, and sums up its core raison d’être in a heartbeat. But there’s a world of difference between tapping Joe Public’s gargantuan, collective knowledge-base on The Three Stooges or quantum mechanics, and mapping out streets, rivers, buildings and canyons on a collaborative canvas in the cloud.

Indeed, any discussion on the rise of OSM and its credentials in the mapping realm needs to look at how exactly it gets its data, and how reliable this data is.

The inner workings of OpenStreetMap

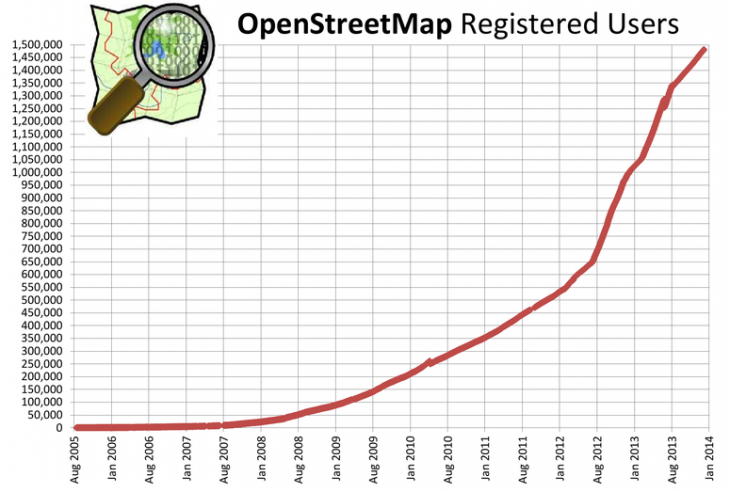

Today, OpenStreetMap has in the region of 1.5 million registered editors, representing a hockey stick-style growth over the past 18 months. As you can see here, there were only around 650,000 registered users in August 2012.

Of course, there are varying degrees of engagement among the editors – just like Wikipedia. “You’ll have a small number of people who sit there editing all day long,” says Coast. “Then you’ll have a much larger group of people editing once a day, once a week or maybe once a month.”

But how does all this data actually get from humans and into the maps? Are they out on the streets with yardsticks and cameras?

“When the project began, then there was nothing at all,” says Coast. “What people did was basically bike around – because biking in Europe is one of the quickest ways to get around. And they’d bike around with a GPS device and a camera, then they would return home with this GPS trace – a series of dots of where you traveled – and then you would match this data to the photos.”

So when things kicked off, it was about as manual a process as you could get. While it still is very much a manual process to some degree, things have evolved over the years to expedite development.

“Now we have access to aerial imagery so you can draw on top of the picture,” says Coast. “That said, some people in some places do still use GPS to map things out, especially if a new road has been built, which isn’t yet included in the aerial imagery.”

You’re probably thinking, ‘Sure, but where does all the aerial imagery come from? Surely there aren’t 1.5 million people hot-air-ballooning around the globe armed with digital cameras? Well, of course not. The imagery actually arrives via a more sensible conduit. “When I worked at Microsoft, we made a donation of all our aerial imagery to OpenStreetMap, and it’s still updated regularly,” says Coast.

Of course, capturing adequate aerial imagery is a tough task for companies of any size. You have to go on days when there aren’t any clouds, while lighting conditions must also be good. Then you have to prioritize areas that change a lot, or are important to people, such as sprawling conurbations. Typically, such images are garnered from airplanes, but satellite imagery is also used sometimes.

But for OSM’s band of merry editors, how the imagery arrives on the platform doesn’t really matter – all that matters is that they have a good, dependable base upon which to build.

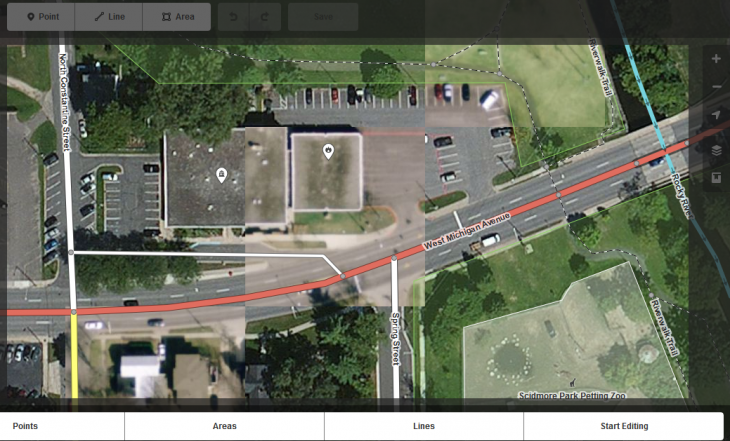

Back in May last year, MapBox launched iD for OpenStreetMap, a slicker editor to encourage more people to contribute to the mapping platform. This was built in pure JavaScript with the d3 visualization library, and was designed to replace a clunkier Flash-based editor – OpenStreetMap adopted this by default just a few months later.

Map features are represented in three ways, using points, lines or areas. Now, points could represent features such as shops, restaurants and monuments, while lines may constitute roads, railway tracks or rivers.

Areas, on the other hand, offer a more detailed way of representing features, and cover boundaries such as surrounding woodland or fields.

You click the segment of the map you wish to edit, and then enter the vital specifics in the left-hand pane – this could be a building name, street name, driving direction (e.g. ‘one way’) and many other data-points that may be of use to the wider public.

This is the very basics of OpenStreetMap, and for most people familiar with other online editing tools, it shouldn’t take too long to get to grips with.

But from an end-user perspective, vis-à-vis those who ultimately end up using the maps to find their way from A to B, how reliable and extensive is the software? And could someone really be comfortable relying on OSM to not get them lost on the way to the airport?

We take a look.